Are Writer-Detectives Reviving a Tired Genre?

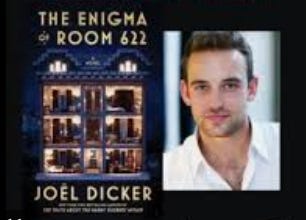

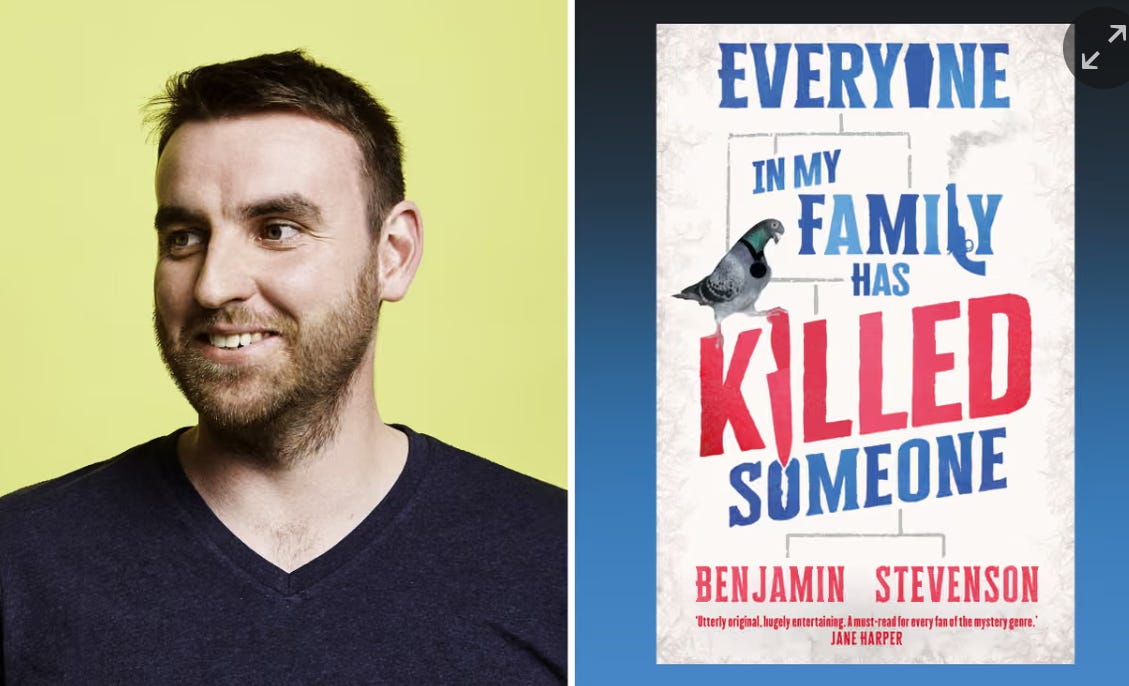

Writer-detectives are making lots of money for their author-creators. Bestseller The Enigma of Room 622 by Swiss writer Jöel Dicker features author Jöel Dicker solving a murder mystery he encounters at a hotel where he’s writing a murder mystery. Anthony Horowitz’ bestsellers in The Word is Murder trilogy narrate the collaboration of author Anthony Horowitz with detective Daniel Hawthorne. Australian writer Benjamin Stevenson adds a load of over-the-top metafictional tricks in his series of bestselling comic mysteries featuring writer-detective Ernest Cunningham. It appears that readers are hungry for tropes that scramble tropes.

Metafiction in crime fiction isn’t new. City of Glass, the first in Paul Auster’s New York trilogy, includes a writer-detective named Paul Auster. Even classic mysteries occasionally raise the curtain a tad to reveal the stage equipment holding story conventions in place. One of the characters in John Dickson Carr’s 1935 The Hollow Man says “we’re in a detective story, and we don’t fool the reader by pretending we’re not.”

The writer-detective trope intrigues by saying two things at once: I’m a real author of fiction; my name appears on this book cover; therefore I wrote this story AND I’m a character in a narrative; this narrative is fiction; therefore I’m fictional and couldn’t have written anything real.

The British novel was born using metafiction to justify its existence. In 18th century novels the found manuscript was a common framing device. The narrative would begin with a prologue in first person telling readers how the not-author discovered this wondrous account in an attic or sea chest. This device says I, the author of this story, didn’t write it. It’s true!

For going on two centuries crime fiction has hewed to conventions of realism that avoid such narrative paradoxes, concealing the story’s fictionality so suspension of disbelief can allow readers to respond emotionally. Why are several of the top crime writers working today flouting all that and making a lot of money in the process?

Dicker’s The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair has sold over 7 million copies in 42 countries. Here young novelist Marcus Goldman has writer’s block and visits his former professor at his beach house. His mentor ends up arrested for the murder years ago of a teenage girl who it turns out he had a clandestine affair with (abused, to be precise). Goldman solves his writer’s block by investigating and writing the story of the investigation which includes the professor’s novel about what happened, a clever mix-and-match of the fictional and supposed non-fictional. Note the allusions to Nabokov’s Lolita which uses the found manuscript trope to give us a story supposedly written by the deceased perp Humbert Humbert, also a literature teacher.

In The Enigma of Room 622 Dicker dumps the facade of a different name and narrates the story of Dicker himself investigating a murder that happened in the hotel room where he’s staying while trying to write a murder mystery.

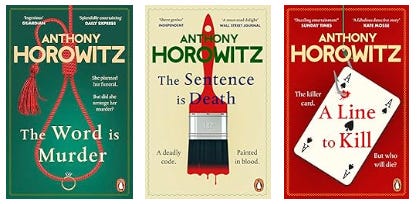

Anthony Horowitz is an old hand at metafiction (see my post: Is Magpie Murders Returning Metafiction to Crime Fiction?), but he takes the further step of introducing himself into The Word is Murder, The Sentence is Death and A Line to Kill where the investigating team is made up of Horowitz and ex-Detective Inspector Hawthorne.

In his Ernest Cunningham series, Australian author Benjamin Stevenson employs every metafictional trope in the book while protesting that he’s telling the truth and returning to the principles of fair play that structured Golden Age mysteries.

In Everyone in My Family Has Killed Someone Cunningham decries the ubiquity of unreliable narrators in contemporary crime fiction and promises he’ll be a reliable narrator. To supposedly play fair he then lists all the chapters where murders will occur. He also admits he’ll kill someone. This is funny, right?

In Everyone on this Train is a Suspect he begins the story with outrageous foreshadowing telling the reader “I’ll end this story in a hospital bed but you know I won’t die because first-person narrators never do.” Then he comments that the first chapter may seem tedious with detail but it’s so full of clues he couldn’t leave anything out. Kirkus Reviews says, “This book and its author are cleverer than you and want you to know it.” The Guardian calls this series ‘excruciatingly self-referential’ but it’s a bestseller and HBO is developing.

Could it be that crime fiction is taking a cue from the popularity of true crime, adopting conventions that create immediacy like heavy-handed foreshadowing, e.g. ‘she would never arrive at her destination.’ Horror movies have been exploiting fake authenticity tropes since The Blair Witch Project of 1999, using techniques that create the illusion viewers are watching videos captured on the run by people affected by the terrifying occurrences.

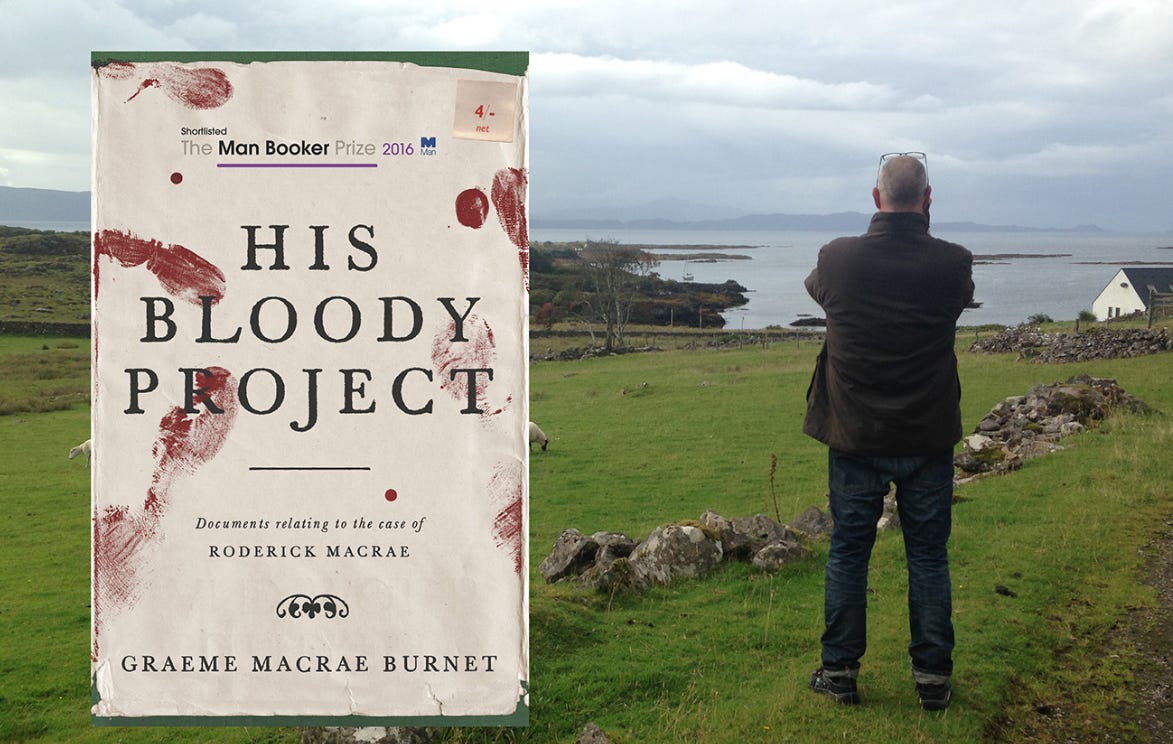

Here’s an example of this in crime fiction: Graeme Macrae Burnet’s 2016 psychological thriller His Bloody Project, shortlisted for the Man Booker prize, pretends to be a true crime compilation of found documents related to a triple murder in the Scottish village of Culduie in 1869 – murders that never occurred.

This mixing of the real and fictional reminds me of the trick author Washington Irving pulled off in 1809 to gain celebrity status for his book, A History of New York: From the Beginning of the World to the End of the Dutch Dynasty, a literary parody. He placed announcements in newspapers seeking the disappeared Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker followed by a fake note from an innkeeper saying if Knickerbocker didn’t return and pay his bill he’d publish his book manuscript to recoup his losses. The public became intrigued. Then Irving published the book under Knickerbocker’s name and it sold like crazy.

All this suggests a response to an audience fatigued with detective story tropes repeated over and over and over to the point of ennui. Stick real authors into their confected narratives. Tell readers who will die when. Point out clues. Give away endings on page one. Break every rule but do it artfully. It’s a bold or cynical experiment and there’s no telling whether it will fizzle when the novelty wears off or spark the creation of new exciting forms. Let me know what you think!

I was completely charmed by the Horowitz books starring himself as Watson to a fictional disgraced police detective Holmes. Lots of other good ideas here for someone with the nerve to play with their audience!

Now I really want to read The Truth About the Harry Quebert Affair