Can Writers Steal Characters?

The Secret Cases of Sherlock Holmes. Did you miss that one when you were devouring the four novels and five story collections Arthur Conan Doyle authored on Sherlock Holmes’ cases? No, you didn’t. Secret Cases, by Donald Serrell Thomas, inserts Holmes and Watson into a fictionalized narrative of some real life Edwardian mysteries. What do we have here? Appropriation of someone else’s fictional characters into non-fictional events to create crime fiction. The fictional becomes real as the real becomes fictional.

Sure, authors have been appropriating the Sherlock Holmes character ever since 1891 when Conan Doyle’s friend J.M. Barrie published “The Late Sherlock Holmes.” Since then Holmes, in the hands of other authors, has fallen in love (Laurie R. King’s Mary Russell series), been reanimated in the future (Sherlock Holmes in the 22nd Century) and appeared with Lovecraft’s Cthulhu monster in Neil Gaiman’s “A Study in Emerald,” 2004 Hugo Best Short Story.

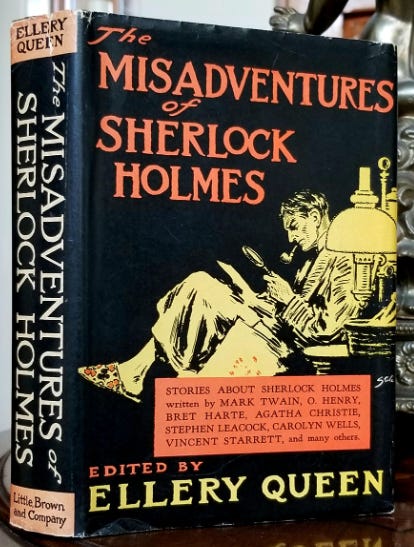

In 1944 The Misadventures of Sherlock Holmes appeared, an anthology of Sherlock Holmes pastiches by famous authors like Agatha Christie and Mark Twain, edited by Ellery Queen (pseudonym of Frederick Dannay and Manfred B. Lee). The Conan Doyle Estate complained and the book was pulled after the first run. In 2014 a US District Court judge ruled the copyright had expired on all original Sherlock Holmes stories except the last ten. They entered the public domain in 2023. Even so, in 2020 the Conan Doyle Estate sued Netflix and author Nancy Springer over Enola Holmes, alleging the more emotional Sherlock in the books and film draws on his characterization in the protected last ten stories. Case dismissed with an undisclosed settlement agreement.

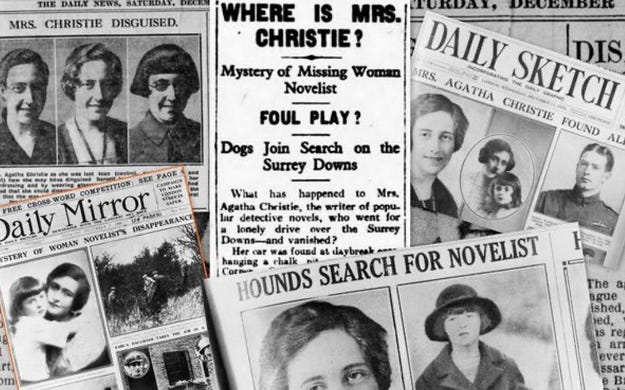

Despite the danger of copyright infringement, crime fiction is full of characters lifted from other works. Even real authors get inserted into novels as fictional characters. In this latter category, Goodreads offers a list of 165 books. For example, The Mystery of Mrs. Christie concocts a fictional investigation of the real documented disappearance of Agatha Christie in 1926. Jane Austen pastiches are legion ranging from Stephanie Baron’s Jane Austen Mysteries to priceless titles like Manslaughter Park (Tirzah Price) and Pride and Popularity (Jenni James). Edgar Allen Poe’s ghost haunts titles like The Tell-Tale Corpse by Harold Schechter and The Tell-Tail (not a typo) Heart by Monica Shaughnessy. Poe’s detective, C. Auguste Dupin, enjoys a continued existence in works like Beyond Rue Morgue Anthology: Further Tales of Edgar Allen Poe’s 1st Detective, with both Paul Kane and Edgar Allen Poe listed as editors although it was published in 2013, 164 years after Poe’s death.

Charles Dickens has also enjoyed extended life in many works of fiction. This conceit bending the fiction-real interface can grow complicated. Take for example a 2015 title, The Hoydens and Mr. Dickens: The Strange Affair of the Feminist Phantom, which contains this attribution: “A secret Victorian journal attributed to Wilkie Collins. Discovered and edited by William J. Palmer.” The book pretends to tell a story about a real historical personage. On the title page it attributes authorship to another real historical person. Then it lists the real author as the manuscript’s editor.

The mixing of fact and fiction goes all the way back to the birth of the novel. Moll Flanders, published in 1722 after author Daniel Defoe had gained fame in 1719 with the publication of Robinson Crusoe, pretends to be an autobiography of Moll. Defoe’s name didn’t appear on the cover during his lifetime, even though he wrote the fictional narrative inspired by interviews with Moll Flanders, a prisoner at Newgate Prison.

Or take Henry Fielding, another 18th century novelist who wrote The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, turned into a 1963 movie, Tom Jones, that won the Oscar for best picture. His novel The Life and Death of the Late Jonathan Wild, the Great narrates the fictionalized life story of an infamous London criminal. No record of libel suits by either Moll or Jonathan, but times have changed.

Is the use of authors or their characters in other works of fiction safe? Copyright for characters described in words is less precise than that afforded graphic characters. Mickey Mouse was fully protected until Steamboat Willie, his first cartoon, entered the public domain in 2024 (after Disney lobbied Congress for decades to extend copyright protections). You can now watch a trailer of a Mickey Mouse horror film or a version of Steamboat Willie full of profanity. Isn’t creativity great?

Legal protection of written-word characters is more fraught. For written works created after 1978, copyright lasts 70 years after the author’s death. Libel protection doesn’t extend after death. But if the character isn’t crucial to the story or lacks definition in the original it may be safe to use. Sherlock Holmes, James Bond, Rocky and E.T. have won cases alleging copyright infringement. Warner Brothers lost a 1954 case against Columbia Broadcasting over use of Sam Spade, the PI from The Maltese Falcon. Since protection of graphic characters is more defined, some experts advise authors to obtain a visual representation of their important characters and then trademark register it.

When appropriated famous characters or famous authors show up in other novels, it touches questions of marketing, copyright and creativity. Marketing because including somebody with name recognition in the story is a way to stand out in a super-saturated genre fiction market. Copyright poses legal risks but is far from clear for appropriated characters in works of fiction. Creativity has been playing with this trope since the novel became a thing, so it’s not stopping anytime soon.