Amateur sleuths are everywhere – everywhere on the internet.

Todd Mathews, considered a founder of internet sleuthing, started trying to identify Tent Girl, a Jane Doe 1968 murder victim, in the 1980s. He only found the victim’s sister in 1998 when she posted on the internet. He went on to participate in the Doe Network and EDAN (Everyone Deserves a Name) where amateur internet investigators work to resolve missing persons and unidentified victim cases.

The WebSleuths site launched in 1999 followed by a trove of subreddits. Now internet sleuthing overlaps with a true crime community that enthralls half the US. While crime novels provide a space for readers to vicariously solve imaginary crimes, these days anybody with an internet connection can try to solve real crimes. Which sounds more gripping?

Internet sleuths solve cases the police couldn’t crack. Joy Baker, a Minnesota mom with a blog, investigated the unsolved disappearance of the child Jacob Wetterling from his family home in 1989. She discovered a pattern in local child sexual abuse cases that led to identification of the murderer in 2014. Other cases, like the disappearance of Maura Murray from a New Hampshire accident scene in 2004, remain unsolved despite years of online attention.

Still other crowd-sourced investigations lead to regrettable effects. After the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, reddit sleuths identified Sunil Tripathi, a youth who had disappeared from the family home, as a suspect and harassed his family members. In reality he had committed suicide and his body was soon discovered. The Find Boston Bombers subreddit issued an apology.

In the 2022 murder of four University of Idaho students, the hashtag ‘Idaho murders’ on TikTok collected over one billion views. A self-proclaimed clairvoyant TikToker accused a University of Idaho history professor of committing the murder. The professor had to take a leave from teaching and dealt with threats to her and her family. She ended up suing the psychic. By contrast, in the Gaby Petito case, online sleuths analyzed photos, videos and other sources like trail registries to help police locate the body.

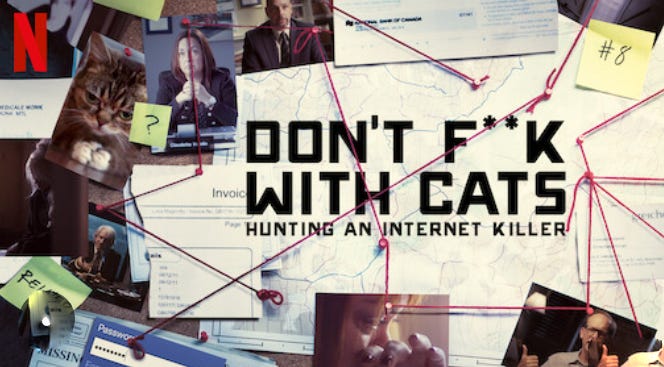

Some say internet sleuthing and the true crime craze manifest an innate human interest in evil. Others say the internet encourages a morbid fascination with gore and violence. Take Netflix’ hit documentary Don’t F*** with Cats: Hunting an Internet Killer charting the real case of murderer Luka Magnotta. He posted videos of cat torture that led to a massive online search for his identity. It might seem laudable that so many are motivated to track down perpetrators of animal cruelty. But when Magnotta posted a video of his murder and dismemberment of a Chinese student to a gore site, the video was viewed over 300,000 times in four hours. That interest has nothing to do with crime-solving.

Sociologists Bradley Campbell and Joseph Manning analyze this trend as a symptom of wound culture. In wound culture victimhood is the focus and confers the highest moral value. Stories of crime circulating on the internet generate victimhood narratives that compel attention and create a sense of solidarity among victims. High profile abuse-murder cases produce loads of comments from people saying the story has given them the strength to remedy their own abuse situation. This suggests that web sleuthing isn’t just an exercise in deductive reasoning. It evokes a collective ritual of possession and exorcism with punishment of the demon and redemption of the victim.

Like it or not this is the environment in which crimes and sleuthing now occur. Is crime fiction catching up? Slowly. For example, Denise Mina’s Conviction portrays an abandoned wife with secrets who becomes obsessed with solving a murder from a true crime podcast after her husband leaves her. Her sleuthing has repercussions for the real-life secret she guards. In Jorn Lier Hørst’s Snowfall a true crime aficionado announces she will publish details about a crime and then disappears.

Governments are scrambling to keep up with the trend by trying to control it. The Canadian government used Magnotta’s case as a justification for a proposed new law granting the government more authority to demand information like IP addresses and contact information from telecommunications entities on users who watch certain videos.

Authors better figure out how to tell stories about internet sleuths who may very well be victims. What do you think?