She was known as one of the four ‘queens of crime.’ Most readers of murder mysteries have heard of two or three of these Golden Age writers. Agatha Christie. Probably Dorothy Sayers. Maybe Ngaio Marsh. But Margery Allingham? My local library offers four Allingham titles of the almost thirty Campion mysteries she wrote, as opposed to over a hundred for Christie. Why did Christie win the century-long popularity contest over her three sister authors who, in their day, enjoyed fame, awards, even bestowed titles?

Christie wrote famously plotted whodunnits, many featuring Poirot and Marple. Sayers brought a literary sensibility to her Lord Peter Wimsey novels along with some snobbery and racism. Marsh followed in the gentleman detective tradition, writing thirty-three novels about police detective Roderick Alleyn, the son of a baronet.

Like Sayers and Marsh, Allingham’s protagonist is a gentleman detective. Albert Campion is upper class and may even be in the line of succession to the throne, although he uses a pseudonym. He’s described as blond, affable and bland with a vacant expression. The BBC adapted eight Campion novels into a sixteen-show series in 1989-90, viewable on BritBox. Here Campion is played by Peter Davison, a British actor who became known for his starring role in All Creatures Great and Small. He’s a balding fellow with blue eyes and horn-rimmed glasses, well-dressed but unremarkable in appearance. Wimsey, Alleyn and Campion all went to Cambridge or Oxford. All served in intelligence. Wimsey and Campion have servant-helpers and drive fancy cars (Wimsey a Daimler, Campion an open-top Lagonda in the BBC series). Spot a trend here?

Contrast this trio of upper class insiders to Poirot. He’s a Belgian (possibly a refugee; many Belgians fled to Britain after the German invasion in 1914), a ‘mountebank’ (a charlatan, one who deceives others), a pint-sized OCD dandy who speaks in broken English to disarm others into underestimating him. In short, a foreigner, an outsider. Then there’s Miss Marple, a spinster, a nosy gossip. She’s not a member of the aristocracy or gentry, nor of the hetero-normative world of married couples. Similarly to Poirot’s affectation of bad English, she chatters about knitting and gardening to make people see her as a silly old woman.

Critics complained that Christie’s characters are composites of repetitive traits (the ‘little gray cells’). They criticized her workmanlike prose. Margery Allingham is a prose stylist. Consider these lines from The Tiger in the Smoke:

“The fog was like a saffron blanket soaked in ice water… the rest was a granular black, overprinted in grey and lightened by occasional slivers of bright fish colour as a policeman turned in his wet cape.”

She varies her presentation of Campion in the novels, sometimes treating him almost like a minor character. Her plotting is diverse. Some are straight whodunnits while others lean toward a thriller plot where the killer is revealed early on and suspense derives from exploring the killer’s personality and watching to see if he’ll be caught. She’s a skillful writer who grew up in a family of writers and published her first novel when she was nineteen.

Yet decades after the Golden Age of Detective Fiction, Christie is legendary while Allingham is barely remembered. Can we draw any conclusions? We’ve all heard that in genre fiction plot rules. But what about the staying power of a character in the cultural imagination? In most crime fiction the detective provides readers a point-of-view for perceiving and analyzing the details of the narrative. But seeing through the eyes of an upper class insider produces tunnel vision.

The BBC series on Campion recognizes this problem and attempts to compensate for the limitations of an upper class perspective through occasional incidents illustrating class conflict. In one scene Campion and Lugg are driving through the countryside. Campion stops the car and tells Lugg to take a bus home as he has changed his plans. Lugg is aghast. “A bus?” he asks. Nothing but trees in sight. Campion simply repeats the order so Lugg gets out of the car and Campion drives away leaving him standing bewildered by the side of a lonely road. Ironically, since Lugg as servant devotes himself to fulfilling Campion’s needs, he is acutely aware of Campion’s feelings and wishes. But the relationship doesn’t force Campion to become conscious of Lugg’s needs and inner world. So Lugg ends up with a greater understanding of their shared world than Campion.

Poirot is an outsider to British society and to the upper class. As a cultural outsider he observes a society not set up to serve him. From this marginal position he can observe the characters circulating around him more clearly than a privileged insider. Miss Marple is also a type of outsider. In a society defined by gender norms, she never stepped into a normalizing category. She moves outside the social world organized around marriage. So both of these characters have out-of-the-box perspectives. Their outsider position allows the reader to vicariously view the relations and actions of other characters in the social world from a birds-eye perspective. A detective on the margins lets us perceive and maybe criticize ‘the way things are done.’ Hence, they’re more fun.

That’s why I think Christie remains so readable while other classic mystery authors may give pause. I’d love to hear how you see it.

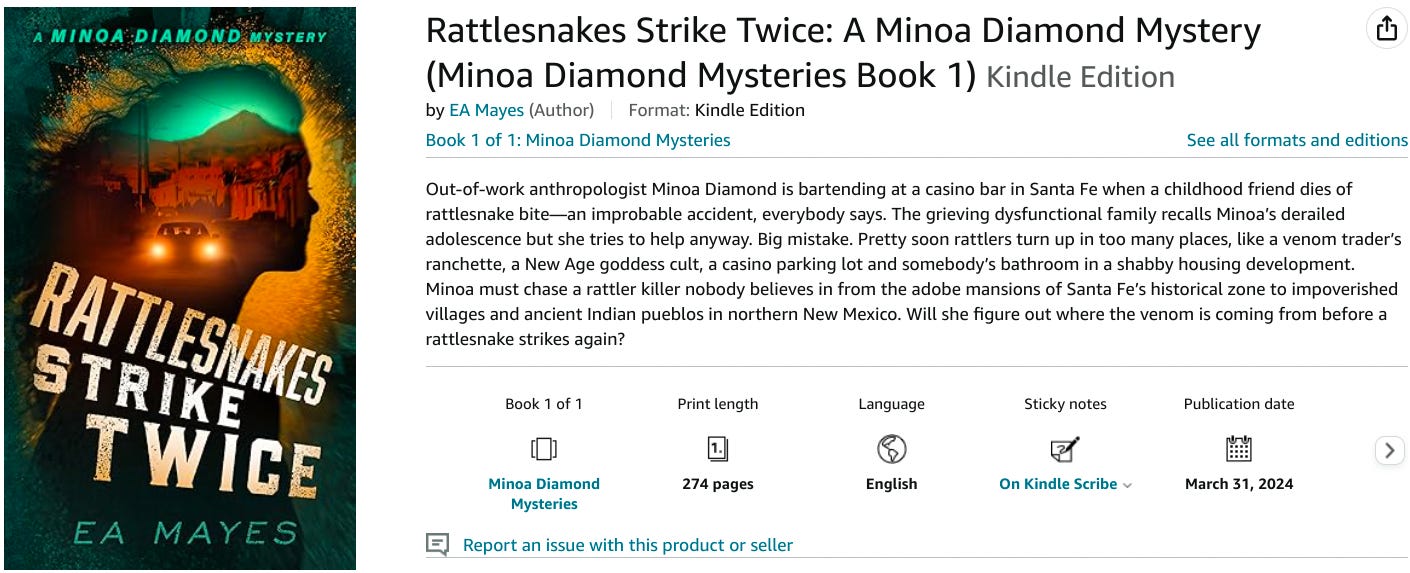

Rattlesnakes Strike Twice is available for pre-order now on Amazon!

I'm glad you're writing about Campion and Allingham. My wife and I have long enjoyed the Campion stories. In fact, she used _The Traitor's Purse_ in one of her courses.

I've read a bunch of the Marsh novels but don't remember them particularly.

The focus on the aristocrats in Sayers and Allingham may have something to do with their relative lack of popularity, but, on the other hand, recent TV shows featuring aristocrats have been extremely popular. And Lugg and Bunter play significant, respected roles in the novels' plots and provide a good counter-balance to the aristocratic leads. Lugg more explicitly with his lip, but Bunter too, despite his impeccable deference, isn't overly taken by Lord Peter. I think one could even say that Campion and Wimsey are caricatures, not too far removed from Bertie Wooster?

So, to return to your question. It might well be the quality of the puzzles that Christie poses. One can come back to a Christie novel after several years and be puzzled all over again. Also, maybe Sayers and Allingham are more novelistic, more complex, than the Christie stories. Your point about Allingham's more artistic style might relate here. If you read Christie you know what you're going to get--a great puzzle and static main characters (Poirot, Marple) who aren't themselves much involved in the human condition. About Holmes too that's probably true.